News | Stories

Lessons From Turkey, Part Two

Earlier this month, Thornton Tomasetti engineers headed to Turkey to collect data on how buildings and infrastructure performed during the recent Kahramanmaraş earthquake sequence, which was one of the worst in recent memory. Led by Managing Principal and Forensics Practice Co-Leader John Abruzzo, Principal Kerem Gulec, Vice President Onur Ihtiyar, and Project Engineer Francisco Galvis, who wrote about the journey. The latest in a series of articles is below.

The World Bank estimates that February’s Kahramanmaraş earthquake series caused more than $34 billion in direct damage to buildings and infrastructure across southern Turkey. The Hatay, Adıyaman, Gaziantep, Malatya and Kahramanmaraş provinces were the hardest hit, accounting for some 81 percent of the estimated damages.

The third day of our reconnaissance mission focused on the city of Kahramanmaraş, which is located between the epicenter of the two main quakes of the sequence. Our first stop was in a small village 15 minutes from the city center to observe a surface failure that shifted the ground about 10 feet laterally and deformed the road. The extent of the displacement was a striking illustration of the amount of energy released in these events. We noticed that in the fields adjacent to the shifted road, the surface failure extended as a band of fractures as opposed to a straight continuous line as is typically idealized in engineering models.

In Kahramanmaraş, the scenes were like those in Nurdagi: several pre-2000 vintage buildings were heavily damaged and in a precarious condition. There were also many parcels of land that stood empty where buildings had been. Multiple excavators continue working in the area collecting debris and the demolition of severely damaged buildings is underway.

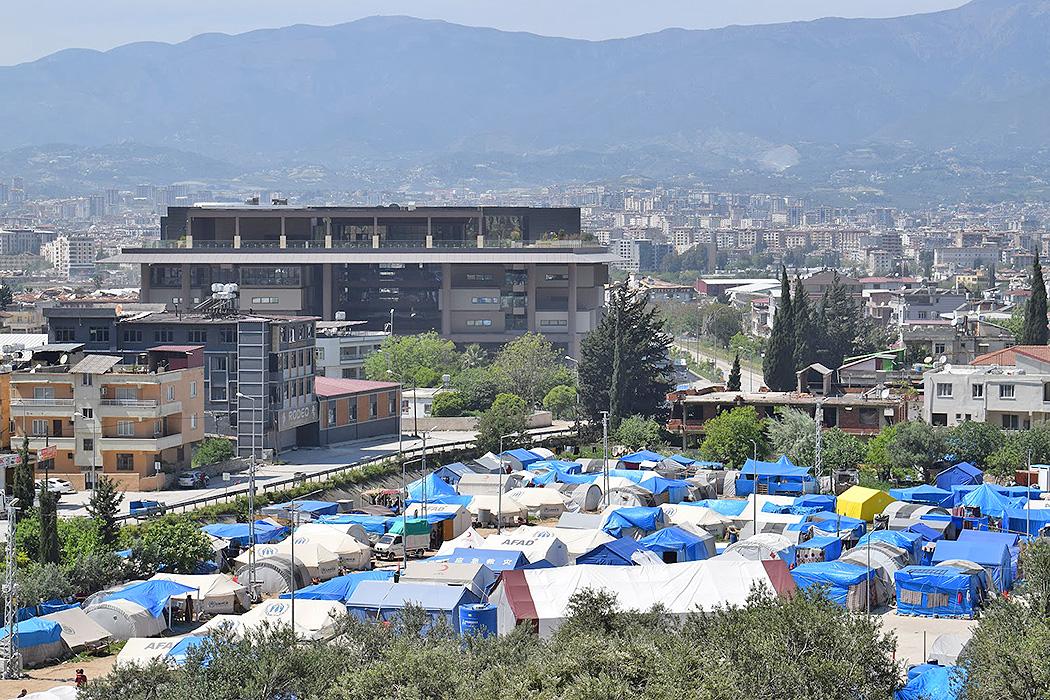

A significant portion of the population lives in tents provided by AFAD (Turkey’s agency for disaster and emergency management) or donated by foreign countries. Some of these tents are in designated areas, while others are in backyards or on the sidewalks in front of the buildings where the occupants presumably lived.

We stopped in one of the city’s post-2000 residential developments, which had several 12-story buildings. The development was in the city’s foothills, and in this area, buildings of all heights performed very well with no signs of damage. We suspect that the ground shaking was significantly lower on the hills compared to the city center. A few blocks away, still on the hills, there were residential buildings of a similar height with minor horizontal cracks on the joints between the façade infill walls and the reinforced concrete beams. There was no diagonal cracking. This appears to be consistent with the effect of vertical accelerations that may be prevalent in this area.

Driving down the hill toward the plains revealed diagonal cracking in similar structures. We inspected a 16-story reinforced concrete building that had been under construction. The building, which was nearly completed with many of its interior finishes already installed, had severe damage but only light structural damage. The foundation was completely exposed with a 90-degree angle cut on the downhill side where the mat of another building was recently built. Across the street from this development, there were older (circa 2005) 11-story buildings with no damage reported by the residents.

We drove 5 kilometers to a housing development in the foothills. Built in 2014, it consisted of dozens of 12-story buildings. Most of them did not have window frames, doors, kitchen counters, cabinets, or piping, as they were actively being stripped of anything of value. A former resident told us that the entire development was deemed severely damaged, and the government promised to demolish it and rebuild it within one year. We inspected one of the buildings and the structural damage was light. The buildings performed as intended under the Turkish building code and FEMA standards. In other words, the structural system was repairable. However, due to the degree of non-structural damage and the fear among former residents to return, the entire development of about 35 buildings will be demolished. We estimated around 7,000 people from this community alone were displaced.

Our next stop included inspecting two precast warehouses used for making yarn. The first warehouse, constructed in 1993, lacked a proper diaphragm, which resulted in excessive displacement of the precast columns and unseating of the girders. This, in turn, caused a partial collapse of the roof. The warehouse next door was built in 2016 with the same system but using longer seat lengths. It apparently had a better connection from the joists to the roof panels that improved the diaphragm action. The base of the columns had spalling, but none of the girders collapsed except for an addition at the back of the warehouse where the detailing did not seem to match the rest of the building.

Our final stop was one of the largest hospitals in Kahramanmaraş. This facility remains non-operational, presumably due to extensive non-structural damage. We were not allowed to enter the building, but damage to the partition walls and suspended ceilings was evident by looking through the windows. There was active construction for a base-isolated addition to this hospital that we were able to document.

The following day we drove southwest toward the southern end of the rupture in the region of Hatay. We made stops in Hassa, Kirikhan, and Antakya. These cities reported the strongest tremors of the event in terms of peak ground velocity exceeding 200 centimeters per second. The level of destruction in these cities, especially in Antakya, was far from what any of us had ever seen before.

In Hassa, we inspected a warehouse constructed with the prefabricated system for the area. In this case, however, the shear walls were not properly attached to the system at the top. The structure suffered a partial collapse. Nearby, there were three 11-story residential buildings. One of them had collapsed and the other two had significant residual drift (between 3 percent and 4 percent). The buildings had a clear soft-story due to the lack of infill walls in a first-floor retail space. Across the street, we observed a five-story government building that had no damage and was operational. It is worth noting that the Turkish building code imposes an importance factor of 1.5 for the seismic design of all government buildings. We saw multiple examples where government buildings performed much better than surrounding structures, which are typically designed with an importance factor of 1.0 (a 50 percent lower resistance to seismic loads).

In Kirikhan, we inspected a six-story residential building that remained occupied. Built in 2005 of tunnel form construction, the structure suffered damage to the mechanical components on the roof and minor cracking on partition walls. Some 12-story buildings nearby that had been constructed later had significantly more damage in infill and exterior walls. In both Hassa and Kirikhan, buildings with three or fewer stories had less damage than taller ones, indicating that the dominant frequencies of the tremors in these areas were in the medium to low range. Of all the sights we had seen thus far during our mission, Antakya was the most impactful.

The majority of the population is living in tents or container housing provided by the government. The downtown area is completely destroyed. Most buildings that remain standing have too much damage to continue to be operational. Officials estimate that some 80 percent of them will have to be demolished.

On top of the disastrous impact these demolitions have on people’s lives and the economic growth of the region, it is also detrimental to the environment. A considerable amount of carbon is going to be released into the atmosphere as these buildings are demolished. It might make more sense to use additional carbon during construction in the form of a stiffer and stronger system or seismic isolation or dissipation devices in order to reduce the potential for damage and demolition following a natural hazard event.

Antakya was the one city where all buildings were damaged as opposed to other cities where it appeared to be less severe damage on low-rise buildings or those near the hill side. Driving though the city felt like we were in the middle of a war zone. But here, too, the community is working hard to recover. Nearly all collapses had already been cleaned up, and heavy equipment was everywhere demolishing buildings and hauling debris.

Our thoughts go out to all those affected by this deadly disaster. It is our hope that the engineering community can apply the data and research from events like this to help lessen their impact in the future.

Related News

Lessons From Turkey, Conclusion

Lessons From Turkey, Part Three

Lessons from Turkey