Arecibo Radio Telescope

What began as a maintenance project quickly shifted to a recovery and forensic investigation.

The Challenge

When the Arecibo radio telescope collapsed on December 1, 2020, plans were already underway for a cable replacement program for the 57-year-old facility. What had begun in August 2020 as an engineering consultation for a cable-socket failure rapidly switched to site stabilization, condition and damage assessment, post-collapse remediation and recovery, and a forensic investigation to determine the underlying causes of the collapse.

Here's How

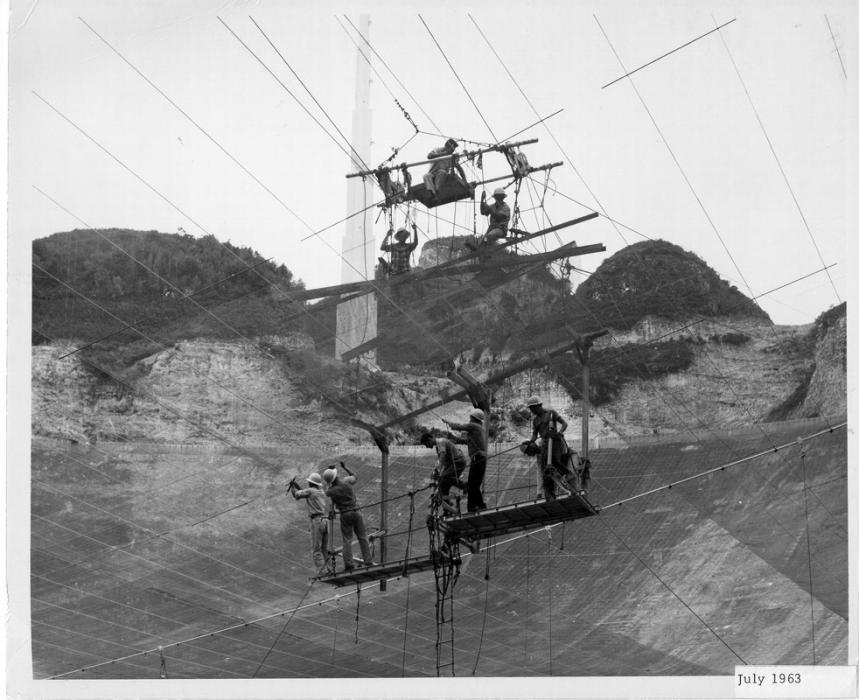

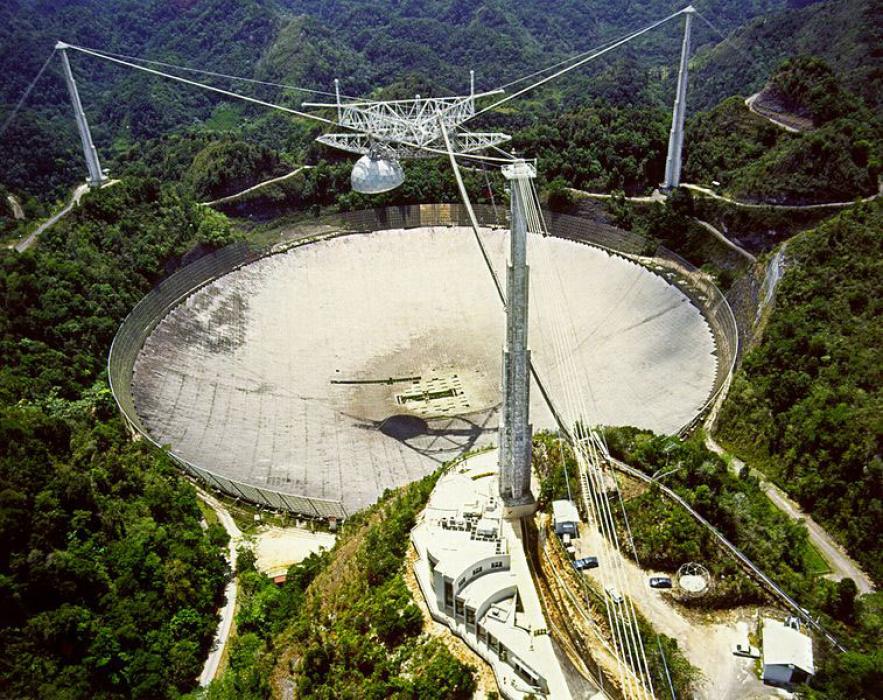

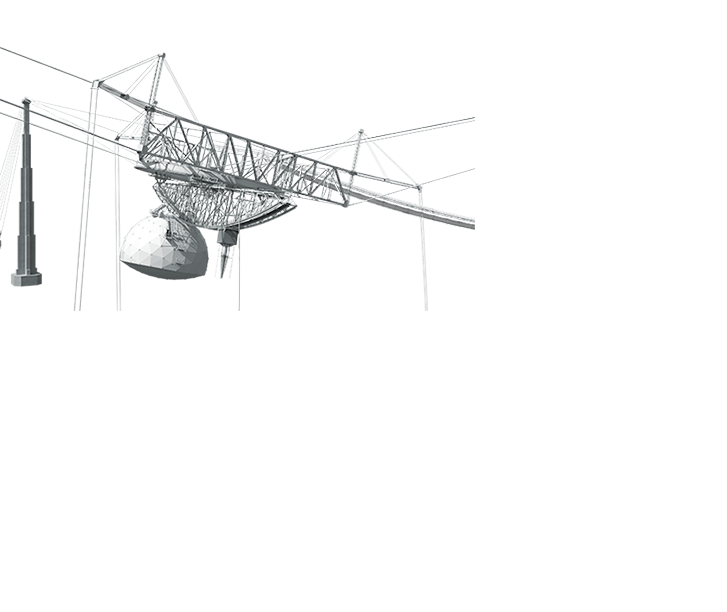

The telescope comprised a spherical reflector that covered an area nearly equivalent to 11 soccer fields, with 18 cables (from towers to instrument platform) suspending an instrument array 150 meters above. Six of the 18 cables had been added in the 1990s to support a 300-ton increase in instrument load. Over the years, cables were inspected, and one (a back stay, which supports one of the three towers) was replaced in 1981.

In August 2020, replacement of a single cable was planned, and proposals sought for the work. But before the job could be awarded, a cable came loose from its socket, putting the replacement program on hold while the project shifted to emergency assessment to understand the effect of the cable loss on the entire structure.

Initially, one of the contractors seeking to perform emergency repairs asked us to support emergency construction services. But at the request of the observatory, we were instead retained by the observatory operator (University of Central Florida) to determine the adequacy of the damaged structure and design the repairs. At this point, Thornton Tomasetti became engineer of record for emergency repairs, construction engineering and final repairs.

To design the repairs, we conducted a structural assessment, refined models of the facility and factors of safety, and produced construction documents. A key approach was to design a cable arresting system – if a cable broke while crews were working on the structure, the arresting system would allow it to slide out slowly, rather than spring out, flail around and possibly injure someone or damage other structures.

New cables were ordered and en route to Puerto Rico when a second cable snapped on November 6, 2020. This dramatically increased stresses on the remaining cables, making most areas of the site unsafe for workers – and making the site, as a whole, too precarious for our original repair plan to be practical.

Could Arecibo Be Saved?

Collaborating with the contractors, other engineers, the University of Central Florida and the observatory owner, the National Science Foundation, we developed a long list of ideas for increasing load capacity and making the structure safe enough to repair. It was a race against time, since the cables' component wires continued to break, further elevating stresses on the remaining cables. All options to save the structure were unlikely to succeed, and wires had begun to break more often due to the higher stress. So just before Thanksgiving, we recommended that the telescope be disassembled.

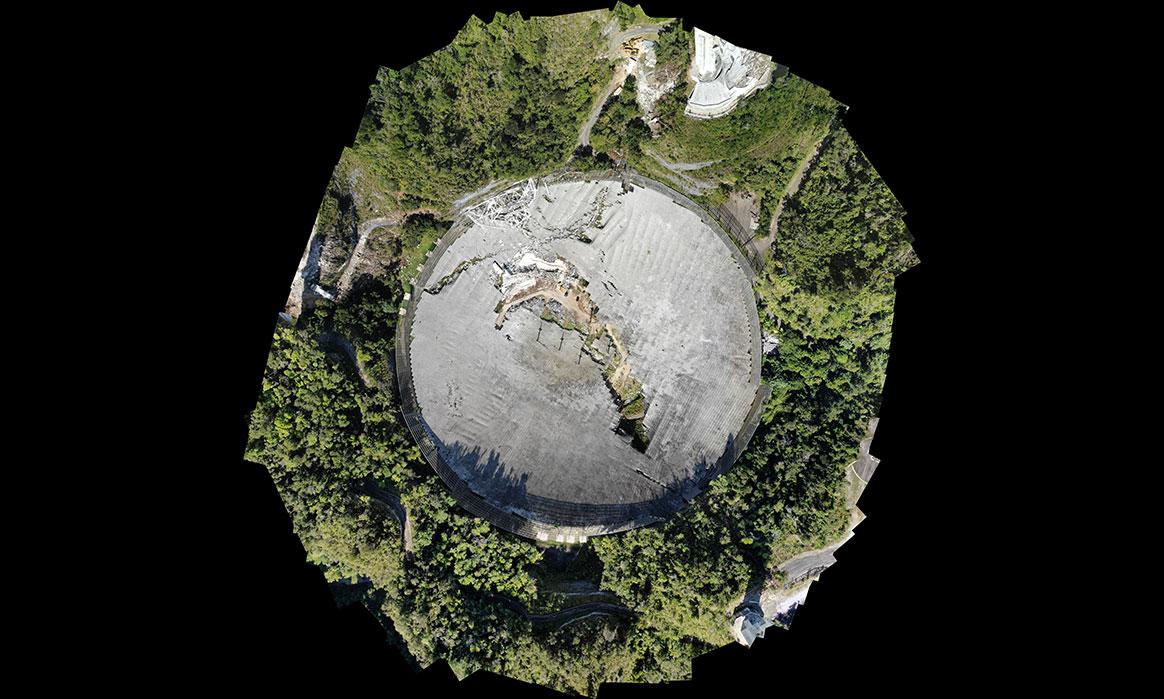

During the fourth week of November, the project team was in constant communication, logging the number of wires broken each day and assessing the state of the telescope. Hoping for the best – and preparing for the worst – we contacted D.H. Griffin, a demolition contractor, to review the situation. On December 1, as our team was driving up the mountain to the observatory, the platform collapsed.

Switching to Recovery

Luckily, no one was near the dish at the time and no injuries occurred, largely because a safe zone, barring staff from areas of potential danger, had been established prior to the collapse .

An immediate concern was an area where soil had been impacted by a few hundred gallons of hydraulic fluid, which fell 150 meters from the platform to the ground. Thornton Tomasetti, Langan, D.H. Griffin and CSA Group conducted a remediation, removing debris from the site to gain access to and remove the impacted soil.

Thornton Tomasetti

Thornton Tomasetti

In December 2021, we began focusing on emergency cleanup activities (removing the fallen structure and tons of steel debris from the site), safety engineering and soil testing, which confirmed that no hydrocarbons had penetrated into the underlying aquifer, and initiated forensic work to determine the cause of the collapse.

The forensic report was released by the National Science Foundation in August 2022.